I am invested in questions concerning all the ways we can do wrong, precisely when we think we are doing right, and including those times when we are in fact doing some things right. To that end, I am most interested in the history of concepts like affect, evil karma, ignorance, and selfhood, especially as they concern feminist and disability interests. My approach to these questions is always informed by at least two traditions, but I am most specialized in the historical relationship between German and Japanese philosophy.

How did a 20th century Buddhist philosopher change his philosophy in response to fascism?

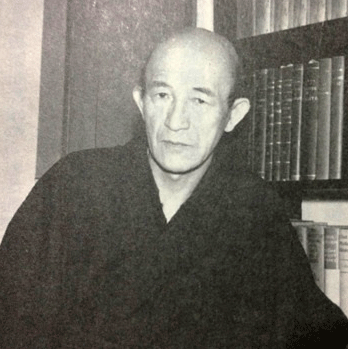

Nishitani Keiji, one of the most influential members of the Kyoto School, developed his own notion of how we relate to one another, which he termed the “emptiness-in-affect” (情意に於ける空), and which is central to the contributions he thought Buddhist philosophy could make to the fields of epistemology, ethics and metaphysics. In Realizing Wisdom and Compassion Through Nishitani Keiji’s Emptiness in Affect (opens in Academia.edu), these contributions are explained in the context of a development within Nishitani’s thought after the Second World War, and then applied to offer novel responses to present-day uses of mythical images in social movements with the aim of improving mutual understanding and care.

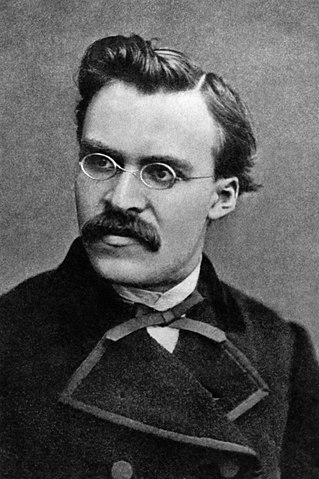

What can Nishitani’s critique of Nietzsche teach us about the concept of space we need for coalition?

Nishitani deems Nietzsche a nihilist, but they both sought to overcome idealism. Nishitani’s view of Nietzsche as a consummate nihilist has, then, a bivalent significance. On the one hand, Nishitani needs Nietzsche’s thought to negate nihilistic conceptions of affect derived from Hegel and Feuerbach. On the other hand, Nietzsche’s negation appears to remain limited by an abstract conception of space, which impedes the full liberation from nihilism through contemporary coalition. In The Nihilism of Idealism in Nishitani’s and Nietzsche’s Passionate Thinking of History (opens in the scholarly collective), the historical connections between these figures are explained and the value of Nishitani’s critique defended.

What can the first woman officially recognized as a member of the Kyoto School teach us about remorse?

Attending carefully to the thought of Shinran, founder of Shin Buddhism, Keta Masako argues that the awareness of one’s own evil should not be abstracted from our ordinary concern with pleasure and pain. She explains that Shinran’s insight into this possibility is based on a Buddhist notion of temporality, namely impermanence, which links the problem of evil inextricably with the problem of suffering. Keta grounds this account with a play on the Heideggerian phrase ‘being-toward-death,’ describing human existence in terms of a ‘being-toward-hell.’ In “The Self-Awareness of Evil in Pure Land Buddhism: A Translation of Contemporary Kyoto School Philosopher Keta Masako” (opens on Academia.edu), the interdisciplinary historical background to Keta’s argument, and some of the technical points of the translation are also explained.

What does a disabled Shin Buddhist scholar have to say about the social model of disability?

Yoritaka Tsunenobu, like many disabled scholars the world over, has proposed a new paradigm of disability theory that seeks to take us beyond the social model of disability without losing all that the model has accomplished. My next long-term research project is to help situate Yoritaka’s theory, which brings Shin Buddhism into conversation with Anglo-American disability rights movements, within the context of recent crip theory. Yoritaka’s list of research contributions can be surveyed on Research Gate, including his 2015 book, 真宗学と障碍者学:障害と自立をとらえる新たな視座の構築のために (Shin Studies and Disability Studies: For the Sake of Constructing a New Position that Comprehends Disability and Independence).