What can marginalized figures in the history of philosophy teach contemporary social philosophy?

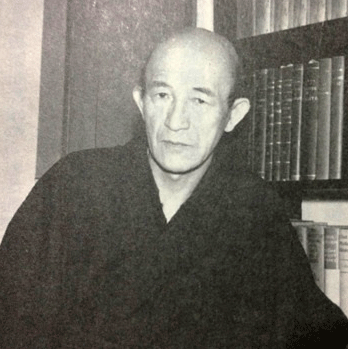

Nishitani Keiji, one of the most influential members of the Kyoto School, developed his own notion of how we relate to one another, which he termed the “emptiness-in-affect” (情意に於ける空), and which is central to the contributions he thought Buddhist philosophy could make to the fields of epistemology, ethics and metaphysics. In Realizing Wisdom and Compassion Through Nishitani Keiji’s Emptiness in Affect (opens in Academia.edu), these contributions are explained then applied to contemporary uses of mythical images in contemporary social movements to improve mutual understanding and care.

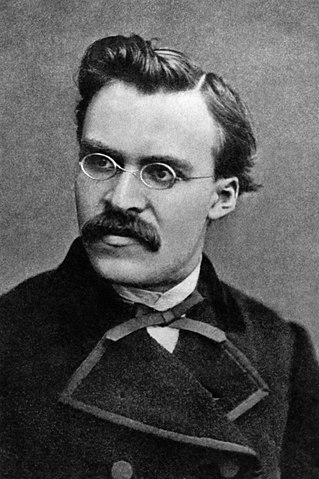

What can Nishitani’s critique of Nietzsche teach us about the concept of space we need for coalition?

Nishitani deems Nietzsche a nihilist, but they both sought to overcome idealism. Nishitani’s view of Nietzsche as a consummate nihilist has, then, a bivalent significance. On the one hand, Nishitani needs Nietzsche’s thought to negate nihilistic conceptions of affect derived from Hegel and Feuerbach. On the other hand, Nietzsche’s negation appears to remain limited by an abstract conception of space, which impedes the full liberation from nihilism through contemporary coalition. In The Nihilism of Idealism in Nishitani’s and Nietzsche’s Passionate Thinking of History (opens in the scholarly collective), the historical connections between these figures are explained and the value of Nishitani’s critique defended.

What can the first woman officially recognized as a member of the Kyoto School teach us about remorse?

Attending carefully to the thought of Shinran, founder of Shin Buddhism, Keta Masako argues that the awareness of one’s own evil should not be abstracted from our ordinary concern with pleasure and pain. She explains that Shinran’s insight into this possibility is based on a Buddhist notion of temporality, namely impermanence, which links the problem of evil inextricably with the problem of suffering. Keta grounds this account with a play on the Heideggerian phrase ‘being-toward-death,’ describing human existence in terms of a ‘being-toward-hell.’ In “The Self-Awareness of Evil in Pure Land Buddhism: A Translation of Contemporary Kyoto School Philosophy Keta Masako” (opens on Academia.edu), the interdisciplinary historical background to Keta’s argument, and some of the technical points of the translation are also explained.